Out of Time

My month in another dimension

The most surreal month of my life was the month leading up to my mother’s death, and it’s because it happened outside of time on some other plane. And it also happened on actual planes that I took back and forth every week from New York City where she was in the ICU, to Los Angeles where I’ve lived since 2001. I’d come home to L.A. for a night, look at my kids, look at my husband, make sure they were okay, and head back to New York the next day. I took red-eyes a lot because it didn’t matter what time it was. I didn’t let myself worry about the cost of taking planes like taxis, I just did what I had to do to be with her. I got texts from close friends who were still part of regular time and it was like receiving messages from another life and another world that I knew was continuing on as mine existed untethered, somewhere else.

The last normal moment I’d had before the time continuum was ripped open was sitting with a good friend having an oat milk matcha latte at Thyme Cafe. Ironic I suppose, though it didn’t occur to me until this moment. That’s where I was when my cell phone rang and my brother told me they were at the hospital and if the doctor didn’t intubate our mother, she was going to die, right then. Our mother didn’t want to be intubated, she’d told us that in August and now it was November. But I listened as the doctor asked for permission to do it anyway, because he suspected whatever was causing her breathing issue, it wasn’t the ALS. I said okay, do it, please do it now in a voice that sounded far away to me. I told my friend I had to go. I drove home in a weird state: racing heart, heightened eyesight and hearing like some kind of wild animal, logical thoughts and lists of things that needed to happen so that when I got back to my house, I knew exactly what to do: grab a bag, put things in it like my toothbrush and something to sleep in, grab my laptop, chargers, wallet. Get online to book a flight, kiss and hug my family, get to airport.

My mother was diagnosed with ALS out of nowhere the summer of 2020, but she didn’t accept the diagnosis. She’d spent all of her life and all of mine being that person who never got sick, never went to the doctor, never exercised, never got a mammogram even though her mother had died from breast cancer - that wasn’t going to happen to her. I told my therapist at the time - I was twenty and had just had a benign tumor removed from my right breast - and she said I should ask my mom what was going to get her if not breast cancer, since she seemed so sure. My mother said she didn’t know, but definitely not that. My mother was impossible sometimes. She was also right.

I’m not going to write very much about this now, but my mother resisted the ALS diagnosis for months, because she had decided what was happening to her was my fault. When she began to have speech issues, when she couldn’t speak without slurring, when she couldn’t swallow, when she had to use paper napkins to wipe the drool from the corners of her mouth because her jaw was slack, when she could no longer eat and needed a feeding tube, when she could no longer dress herself easily or make it to the bathroom on time, all of this was because of me. I can’t explain the way this made my brain implode, or how hard it was to accept and still fight like hell for her, but I did it and I kept doing it and I’d do it again. Even after she accepted she had ALS, she never stopped blaming me for it, or making sure that I knew she blamed me. Not until the very, very end did she relent.

I don’t know how to explain my relationship with my mother in a way that anyone outside of it will understand, though I’m currently writing a whole memoir about it. Certainly it helped when I remembered her thirteen-year-old self was often running the show. She was a force in my life and I adored her but I also had to keep myself safe around her. She treated me badly but wanted me to act like she was good to me. She would go for my jugular but god help anyone else who hurt me, because she’d go to war on my behalf. She could be vicious and cruel and she scared me. For a long time I thought Chardonnay was more important to her than I was - she absolutely prioritized her relationship with it over her relationship with me - but she did love me in her own intense, twisted way. I didn’t understand this as a kid, I grew up thinking there was something irrevocably broken at my core if my own mother couldn’t love me, and I played that out in my adult relationships until I realized it was my mother who was broken, not me. But if I could play the game the way she wanted - and that meant agreeing that she wasn’t an alcoholic even though anyone could have told you she was if they were honest and not terrified by her - then she was good to me, but cautiously. We did not have trust on any timeline.

In her mind, my need for boundaries as I got older was a betrayal. There shouldn’t be a need for boundaries because she wasn’t an alcoholic, that’s the line I was supposed to toe. In my mind and in my lived experience, anytime I was near her I was at risk of being hurt, badly. The risk would increase a millionfold if she was drinking, but even sober she could turn on me. So how can I explain to anyone what had me racing to the airport over and over and over again? She was my mother. When I made her laugh, it felt like every good thing in the world. We understood each other on some deep, unspoken level. She hurt me and my job was to allow her to hurt me but still know she loved me. My job was to show up no matter what she did. My job was to pretend things were not what they were. But the love was real. People who love alcoholics may understand this. People who love a person who can never be wrong may understand this, too.

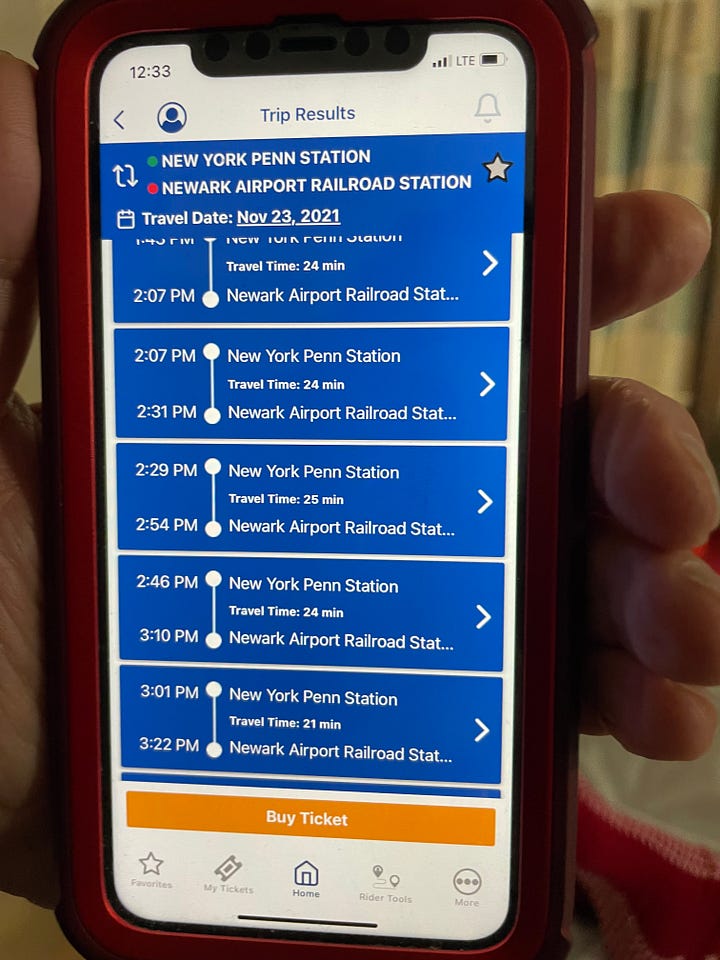

The flight from LAX to Newark Airport takes about six hours, but to go door-to-door from my house to the hospital took more like ten hours, sometimes eleven depending on traffic and timing in either city. My mother was first taken to Lenox Hill Hospital, and that’s where I went that first day to find her unconscious in a bed with tubes everywhere and a machine breathing for her. I hadn’t been breathing normally since the call from my brother, who was asleep when I got there - he’d been up for hours at that point. My stepdad was pale. The doctor came to give me an update not long after I arrived. My mother’s sodium levels had dropped dangerously, that’s what had caused the sudden breathing issues, that’s why she’d needed to be intubated. They weren’t entirely sure what was going to happen, but they were working to raise those levels.

I texted my Aunt Louise and my cousins and told them they’d better come. I texted my husband and kids to let them know I’d arrived. My brother filled me in on the morning and the way things had taken a drastic turn. The previous week had been bad, I’d noticed when we were zooming. She was having a hard time holding her head up, and she’d become very weak. Still, none of us had imagined we’d be in the hospital so quickly. Suddenly across the room I saw my mother’s eyes open and I was saying Mom, Mom, running across the room to her. She looked at me. Her huge brown eyes had turned a bit cloudy. They had a blue tint to them that had never been there before, the way babies with brown eyes sometimes do before they turn brown for sure. I took her hand carefully, making sure not to disturb the IV or any of the wires. We have the same hands, just hers are older. We have the same torso, the same pronounced collarbone, pointy elbows and tiny wrists. Hugging her used to be like hugging myself, but now she was just bones and skin and big scared eyes in a bed. She was disoriented and she looked tiny, like something I needed to protect or it might break. “You’re in the hospital, Mom, everything is okay. You were having trouble breathing, but it isn’t the ALS, your sodium levels dropped. They’re raising those levels now and you’re going to be okay, do you understand?” My mother nodded, almost imperceptibly, but enough. I squeezed her hand gently.

My Aunt Louise arrived not long after, or maybe it was hours later, along with two of my cousins. I knew it would comfort my mother - my Aunt Louise was married to my mother’s only brother, my Uncle Richie. My mother was the flower girl at their wedding. My uncle was eleven years older than my mom, they had different fathers but the same mother, just like I’m eleven years older than my brother, and we have different fathers, too. My mom and dad split up when I was four, and my first husband and I split up when my son was four. I sometimes wonder what gets passed down besides genes. My mom grew up with my Aunt Louise. My Uncle Richie died of a heart attack when I was seventeen. I’ll never forget the phone ringing in our house, hearing my mother pick up in the living room. That was the first time I heard my mother yell out in shock in a voice I didn’t recognize, oh no, oh no, no, and the first time I saw her cry. Since I couldn’t call my mother’s mother - my Nanny - I called Aunt Louise. It did comfort my mother, and it comforted me, too. These are the people I spent my childhood with, on the Jersey Shore. These are the people who knew my mother when she was Cath or Cathy, not Catherine. These are the people who call me Ally-oop and always will. These are the people.

My mother’s neurologist called. He wanted to have her transferred to Mount Sinai on 16th and 1st Avenue because he was affiliated there and could oversee her care. He said he was going to arrange an ambulance for the transfer since my mom needed the ventilator to breathe for her. My Aunt Louise and my cousins left. I explained to my mom what was going to happen, because the doctor had talked to us outside the room. I told her not to be worried or scared, the transfer was just so her doctor could be in the loop and advise about her care. My brother and I sent my stepdad in the ambulance with her and walked from the upper east side to the lower east side - it was going to take time for them to check our mother in and get her settled, and we weren’t going to be allowed to see her until she was in her new room. Walking felt like a good option, it gave me time to process what was happening as I walked the city streets of my childhood. I had no idea Mount Sinai is where I’d be spending the next month of my life, or that it would be the last month of hers. She died two years ago today, December 7th at 3:37am.

Mount Sinai is on the corner of 16th Street and 1st Avenue. When you walk in there’s an inner lobby, and then the main lobby with a big, curved desk. There’s a tiny room to the right with vending machines full of things you probably don’t want. There are fluorescent lights, but that’s the case in every hospital I’ve ever been in. There’s a roped off line to check in at the desk so the person behind the desk can make a copy of your ID and give you a visitor’s pass to stick on your clothing. When you’re going to the ICU, you have to be on an approved visitors’ list and you have to check in, every time. This was also at the height of the pandemic, so masks were required everywhere inside the hospital, but most especially the ICU.

They had moved my mother into a private room directly across from the nurses’ station. I imagined the most precarious cases were the ones closest to the nurses so they could get there quickly. Though it was a private room, it was surrounded by thick curtains, not walls. The curtains facing the nurses station were mostly open, unless the patient was sleeping or being changed, so I could see some of the patients around her. No one looked well, most people were on ventilators like my mom. There was the constant beeping of machines keeping people alive, the rhythm of oxygen being pushed into lungs and carbon dioxide being sucked out. Alarms that would go off if someone leaned on a tube they needed to keep them breathing. The sound of nurses in constant motion keeping track of everyone and also talking quietly amongst themselves. I studied everything, trying to understand where I was, where we were.

The hospital social worker came and introduced herself. She said we’d be meeting with the team of doctors who would oversee my mother’s care for a week, and each week my mother was there, the team would rotate. This way there would be many experts involved in her care, and fresh eyes on the situation each week, if her stay ended up being an extended one. The head doctor of each team would meet with us each week after they took over and had a chance to examine my mom and consult with her neurologist. She showed us the visitor’s waiting room where people could wait to visit if my mom was sleeping when they arrived, or if we needed to rotate. There could only be two visitors in her room at any time.

My mother had to have headgear along with the ventilator, because her jaw was slack. She had a sponge-like catheter system because when you’re on a ventilator, there is no getting out of bed. I learned how many pillows she liked to have when she was sitting up (four) and how she needed them positioned to be comfortable. I learned how to lift her up if she slid down too far and felt uncomfortable. I learned how to adjust her when she wanted to sleep. I rubbed lotion into her legs and feet and put extra blankets on the bottom of her bed if she was cold, or removed them if she was hot. I learned some people cannot handle being near someone who is suffering this way, no matter how much they love the person. I learned how to hear things and have conversations that seemed impossible. I know how to handle trauma, I’ve been doing it all my life. I know how to stay focused in the middle of a nightmare, in the middle of a storm, in the middle of the biggest heartbreaks. It doesn’t mean I’m okay, it means I know how to function and how to keep going and how to pay attention to what needs to happen next.

Time is especially different in the ICU. It has its own ecosystem. It doesn’t matter if it’s day or night, and you can’t tell, anyway. I tried to explain this to my husband and he said oh, like Vegas? And yes, like Vegas except there’s no color, the color has been stripped out of everything and no one wins and what you’re gambling with is your life and what you’re counting on is other people’s kindness. ICU workers, people who actually choose to be there, are some of the kindest people anywhere. Also, some people enjoy Vegas and no one wants to end up in the ICU. Otherwise it’s exactly the same. I would get to the hospital about 9am, and leave when visiting hours ended, at 9pm. Walking to and from the hospital became my tether. Those familiar with New York City will understand what I mean when I say I walked from 85th and West End Avenue to 16th and 1st Avenue every morning and every night. I don’t think I would have made it without the walks. The air is different inside the ICU. Twelve hours doesn’t feel like twelve hours. I couldn’t eat as my mother lay dying. I had no appetite and even more, I just could not do much to sustain myself as she was moving farther and farther away from me, away from this planet. Two of her best friends were there with me a lot. They would bring me a coffee or sometimes nuts, just something small to try to get me to eat. They’d text to ask what they could bring me on their way in, but I always said nothing, but thank you. There wasn’t anything.

In the mornings I’d walk across Central Park. This happened to be my favorite time of year in New York City, the time leading up to Thanksgiving and all the holidays. The time of year when the city I love like a person puts on its fanciest outfit. Macy’s gets dressed up. The tree at Rockefeller Center goes up and there’s a lighting ceremony. Fifth Avenue is strung up in lights. All the stores create their most amazing windows. People ice skate at Rockefeller Center and Wollman Rink (it will always be Wollman Rink to me). The air is crisp but it isn’t freezing yet. You’ll get plenty of sunny, cold days. I used to walk across Central Park on my way to high school, with my Walkman playing Yaz, Sting, Depeche Mode, or James Taylor if I was feeling down, which was most of the time. The walk across Central Park lives in my bones. Sometimes I felt I was meeting my fifteen-year-old self as I walked. This time - as a grown woman with my own children in high school and middle school, I’d take pictures so my kids and husband would have some connection to what I was living. I didn’t want them to have too much of a view, especially my kids. I didn’t want them to see their grandmother this way or see me this way, because on some profound level I felt the ground slipping out from under me. I was hurtling through space, occasionally managing to grab onto something that felt solid. My mother didn’t want to Facetime with my kids because she didn’t want them to remember her as she was, so she just listened to them on the phone and I’d tell them she was smiling or nodding. She’d gesture for me to tell them she loved them, which I did. I can’t and won’t share pictures of her at the end of her life because they are heartbreaking and devastating. When I went to find the pictures of New York that I knew I had on my phone from this time in my life, I saw pictures of my mother that are so awful I can’t believe we didn’t see that she would never make it home.

I see social media posts pretty often these days where someone will be visiting New York City for an anniversary weekend or to see a show, and someone else will ask under their post if they feel safe. The city feels no more or less safe than it ever did. You have to keep your wits about you like you do in any big city. I walked home every night from 16th and 1st back to the apartment where I grew up, a good six miles away. I would walk up Lexington Avenue and slowly cut over toward 5th Avenue and then 8th Avenue and usually walk right through Times Square as I made my way up the west side. This is usually when I’d call my husband and kids, unless I was done in. It’s hard to explain the mental state I was in after these days. I needed the city, the energy of it and even the weird dichotomy of the colorless, timeless ICU and the pulsing extra-vibrant holiday city. It somehow kept me connected to life. It was comforting to see that people were still living, that the holidays were still coming, that somehow the earth would keep spinning even if my mother wasn’t on it, because I often felt as she was dying that something inside me was dying, too.

I spent so much of my life pushing back against my mother. Moving three thousand miles away from her so I could breathe and figure myself out, even though all I ever wanted was to be close to her. Learning how to trust myself and trust my ability to perceive reality clearly, and to be happy in spite of her not loving me in a way I desperately wanted and needed. I spent so much energy constructing and maintaining boundaries, grappling with the fact that I couldn’t change her but I could change the way I responded to her. People who took my yoga classes knew about my mother because I would share about loving an alcoholic and how hard it is. I would talk about the effects of being told things are not what they are for your whole childhood, the way it teaches you not to trust yourself. The way you might have to reality-test for a long time, and start a million conversations with, is it just me, or….? The frustration of having a mother who was never wrong. I would talk about the gift it was when I walked into a yoga studio and began to understand that the practice was about seeing things as they are, which isn’t always the way you want them to be, and figuring out how to show up with love and an open heart, anyway. My mother was a mythic creature to anyone who practiced with me. I didn’t know quite who I would be without having her to resist and maneuver around.

The city was keeping me grounded. The sounds and smells and energy of it. That was the oxygen I needed, and the food. Calls and quick trips home to my husband and kids felt like taking huge gulps of air that lasted just long enough until the next week, and the next flight home for an overnight, but being away from my mother for too long didn’t feel possible or okay. I’d land at LAX and Facetime her as soon as I was outside the airport. She couldn’t speak to me of course, but I’d say hi, tell her I’d landed, remind her when I’d be back, tell her I loved her. It would almost feel strange to me that our house was still there, along with my kids, husband, dog. I needed to see them and I needed to hug them and know they were solid, warm, alive. It was like landing back in the here and now for a minute, knowing it still existed. Even then, I was never out of touch with her doctors, with the hospital, with the social worker.

So many things happened in that month. My mother got pneumonia in one lung, then the other. She pulled my mask off my face one day and looked at me with so much love and tenderness while she stroked my cheek, it broke me open and I sobbed uncontrollably and kissed her bony hands. She hadn’t done that kind of thing since I was a tiny child. We got right with each other - any misunderstanding she’d had about how I felt about her or how much I loved her was cleared up. She knew it had been the drinking and the rage that had kept me away, not any lack of love for her, and I saw that she loved me even if everything had gotten screwed up. They managed to get her off the ventilator after ten days, with the understanding that she'd need the bipap machine for twelve hours each day, but she wouldn’t have it. She’d use it for fifteen minutes and make them remove it. She would scribble notes on a pad that started to make less and less sense because the carbon dioxide was building up without the bipap machine to clear it. She thought her dog Laszlo was being crushed in a herd of elephants. She thought she was in the basement of the building on West 85th. I could see she was leaving us. I didn’t know how the timeline could possibly continue without her.

I won’t write about the last day, how I’d ended up in Los Angeles thinking we’d get her home for hospice care that Monday, but how everything took a turn and I flew back hoping I’d make it in time. Her best friend held the phone up to her ear even though she was asleep and I told her I was coming, to hold on if she could, but that if she needed to go it was okay, even though it wasn’t. It was not. It would not have been. I told her I loved her and spent the longest twelve hours of my life flying back with one prayer in my head on repeat: Please. I made it back, she was still alive when I burst into her room after midnight, I could still feel her. I held her hand and whispered in her ear. I told her not to be scared, that I would take care of my brother and my stepdad, that she could go now. I told her her mother was waiting for her and her brother and her dad, and I hoped it was true. I told her I loved her so, so much. My brother and stepdad fell asleep about 2am. I held my mother’s hand and stroked her hair and kept telling her it was okay. It was the two of us when I came into this world, and the two of us when she left it. I miss her more than I can say.

If you’d like to meet me in real time to talk about grief, loss and time, I’ll be here Friday 12/8/23 at 11:15am PST, or you can wait for the Come As You Are podcast version. If you’d like to meet me in Portugal in June, I would love that so much.

Ally you are incredibly strong to relive this & especially today on her anniversary! I give you light & love 💗

Awwhhh so many truths to be told. Been through and going through them, so many of them. Thank you for putting words to your truths! Love how you’re able to stay here and inside your experience with raw and real humanity! Love and lightness ✨🫶🏽