Reconciliation

The art of allowing many things to be true at once

My dad died on July 15th, 2023, at about 2am. The hospice team started calling me at 3, then 4, then 5am, but I slept through the phone vibrating on my bedside table, so at 7am I was startled when my husband gently shook me and said there were two police officers at our door - two police officers who wanted to speak to me. In my sleep-haze I thought something must have happened to one of our neighbors, or something must be happening on the block, but my husband said, “I think it must be your dad,” and instantly I knew he was right.

I padded down the hall in my pajamas, not sure if I should be embarrassed not to be wearing a bra. There were two police officers waiting inside the door, one so tall and big it was like he was taking up the whole room, the other shorter and younger. They both looked miserable, nervous and sympathetic. “It’s my dad, isn’t it?” I asked, trying to save them the discomfort of having to tell me. “Yes,” the big one confirmed. “We’re so sorry for your loss,” the shorter one said, and he did look very sorry, and very young. I thanked them. I felt sorry they were in the position of having to deliver such dreadful news. “It’s okay, it isn’t unexpected,” I said, “he was ninety-six.” But I felt dazed.

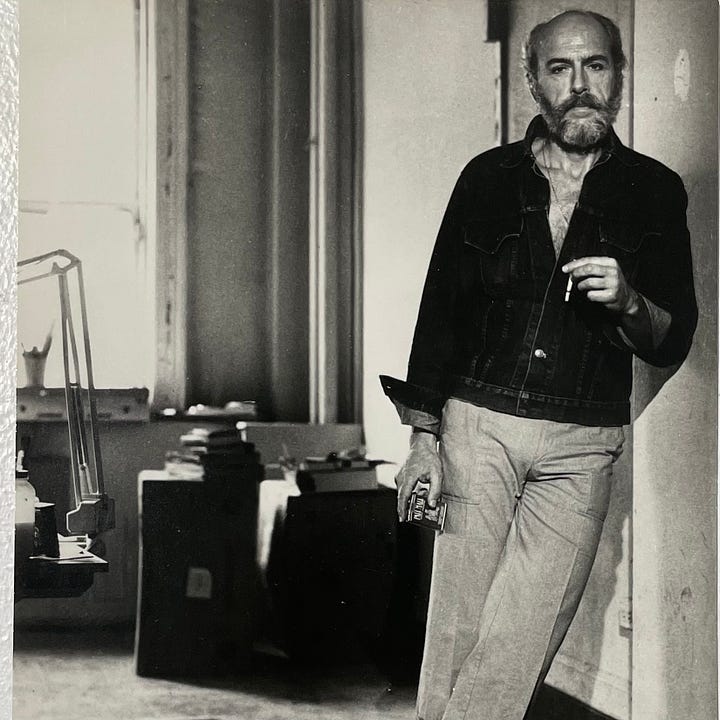

After nine months of looking after him, of taking him to doctors appointments and out to lunch, to Walgreens and Dunkin’ Donuts, after making sure he had everything he needed, sending him deliveries of Mott’s Apple Juice (every other week), clay when he was still sculpting, new sweatpants, a beard trimmer (I accidentally sent one made for manscaping the first time, much to the amusement of my teenagers), a very long shoe horn when his legs started swelling from congestive heart failure … after nine months of driving to the Valley every week and trying to stay on top of anything and everything he needed … he was gone.

I’d seen my dad the Sunday prior and we’d had a good visit. He was weak and in bed, but alert and happy. So alert we were able to FaceTime with an old friend of his. It made his month. It was hard for him to speak, he didn’t have the energy to take a deep breath and project, but if I leaned my ear in close to his mouth, he could whisper to me. “This caught me off guard,” he said, and I knew he meant dying. Somehow, three days short of his 96th birthday, he seemed surprised by what was happening. My dad has always been a dreamer, an idea man, an artist. He was still scribbling ideas on the backs of napkins days before his death. “Your body is just tired, Dad,” I said, “you’re almost ninety-six,” and I smiled as reassuringly as I could. He nodded at me. He seemed grateful I didn’t try to tell him he wasn’t dying, and that he didn’t have to expend the energy explaining what he meant when he said it caught him off guard.

Tuesday of the week leading up to his death was also a good day. He was in good spirits, wanting to know how the kids were, how my husband was, how work was. Thursday was his 96th birthday, which he announced to one of the hospice team when she arrived that morning. That afternoon I went to visit him with my fourteen-year old. We brought my dad rice pudding (always a favorite and easy to eat), a birthday candle, and a helium birthday balloon. When we got there, he was so deeply asleep he could not be roused. Not even when the aide came, removed the oxygen from his nostrils, washed his face with a warm washcloth and yelled, “Alan! Your daughter is here!” right in his ear. “It’s okay,” I said, horrified, “really, please let him sleep.” We left the balloon hooked to the foot of the bed. I hope he saw it at some point.

Friday I knew he was going. I texted the hospice team: We’re at the point where he’s just going to fall asleep and drift off, aren’t we? I am trying to mentally prepare. It’s okay, I just feel very sad thinking of him there in that bed. They told me it was so hard to say. He could go on this way for weeks, they’d seen it before. But I knew. After the police left Saturday morning, I got dressed and my husband and I drove to my dad’s. I felt I needed to say goodbye, even if he was already gone, but I was worried for myself. I was in the room when my mother died, holding her hand and stroking her hair and telling her not to be scared, but when they took the bipap machine off of her, I was not prepared. The look on her face was not peaceful. It haunts me to this day.

My dad’s face was not like that. I don’t know if it’s because he didn’t suffer, though I like to think that’s the reason. I said goodbye to him. I cried. I’m crying as I write this because it feels impossible that my parents are no longer walking on the same planet where I reside. And because I know one day, hopefully one day way out ahead of me, my children will also have this experience. Being human is such an incredible ride, it’s so wildly interesting, but I don’t think anyone would argue that it’s easy. We’re all so vulnerable and so fragile, but we think if we pin down our Monday plans we’ll be okay.

Here’s the thing, or at least one of the things: I was not sure how I would feel when my dad died because my relationship with him was so complicated. My dad almost single-handedly made it impossible for me to have any kind of innocence as a child. He started talking to me about his grown-man problems when I was four, right after my mom and dad split up. That happened the week after my grandma died. My mother did not want her mother to know that they were heading toward divorce. That she was going to be twenty-eight, without her mom, caring for a four-year-old on her own. My mother’s dad had died long before, when she was thirteen. My heart hurts for my mom thinking about how utterly alone she must have felt, even though she had family who loved her, and wonderful friends. Being a single mom in New York City at twenty-eight when your heart is broken because your best friend in all the world, your mother, just died at 58 and your husband, 19 years your senior, could not keep his dick in his pants. Your husband whom you adored. Your husband, who had cheated on his first wife and left his first family, his 16-year-old daughter and 14-year-old son to be with you, had done exactly to you what he’d done with you. Because why? Because you’d had the audacity to get pregnant?

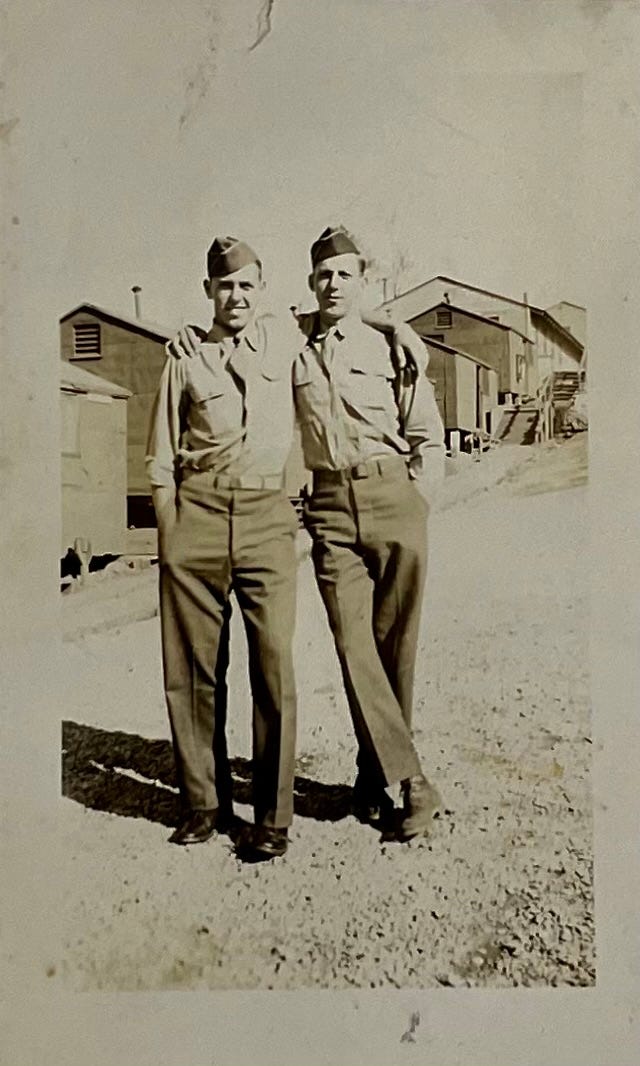

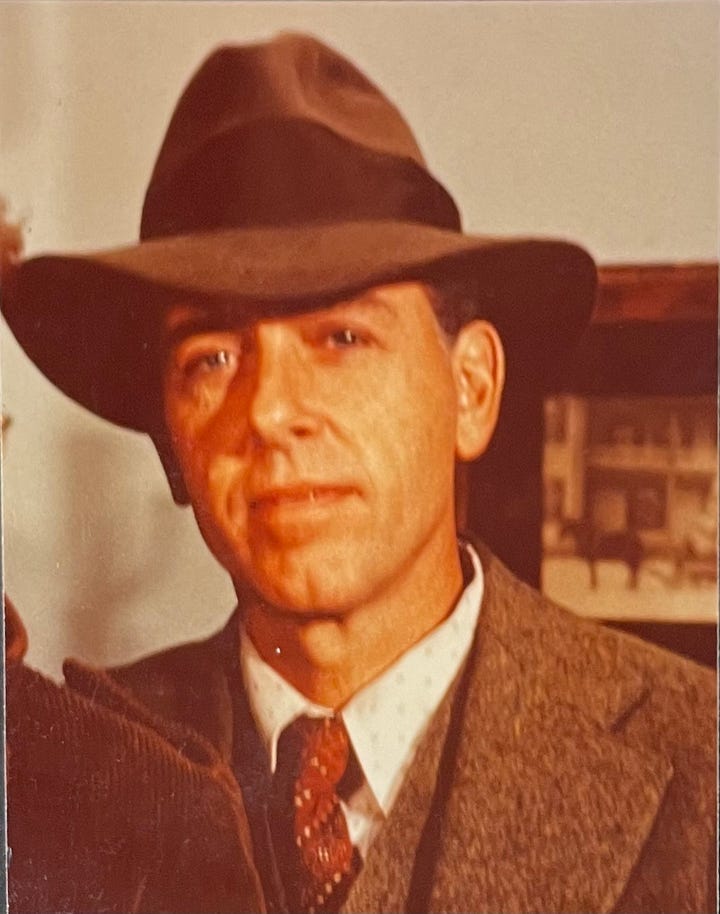

I think I thought my dad hung the moon when I was little. He was an artist, an actor, a writer. He had a twinkle in his eye and he was not afraid to be silly. He would carry me on his shoulders, he would read bedtime stories to me at night. Women loved him, he was dashing and charming and he called all his lady friends you little honey or you little sweetheart. They all looked at him like he hung the moon, too. My dad moved into an apartment with his new girlfriend as soon as he left me and my mom. The next time I saw him he was already living with H. She was a year younger than my mom and looked at him with such love. But it wasn’t enough for him, he told me he needed to be free, he couldn’t commit. And he would sob in my arms. I felt so bad for my dad. I couldn’t understand why all these awful women wouldn’t just share him.

I became my dad’s wingchild, which is instantly underlined in red, because that is not a thing. Spellcheck wants me to fix it, but I can’t because I can’t go back and tell my dad he shouldn’t talk to me about such big and scary grown-up things. He shouldn’t cry in my arms, he’s getting it backwards. My dad would pick me up from my mom’s and we’d go see his lady friend Barbara, or Candace or Dana or Mandy. I couldn’t remember all their names and they changed all the time, anyway. But they were always young and skinny with long hair and big boobs. My dad told me that’s what he liked. Then we’d go home to H. and she’d ask what we’d done and my dad would say we’d gone to the park or the museum, and she’d tell him what a wonderful dad he was. I wouldn’t say anything at all because my dad told me even though these ladies were just friends, H’s feelings would be hurt, so it would be our secret.

Anyway, this madness went on until I was thirteen and I told my dad I was done. I didn’t want to hear about his problems or be his therapist, I didn’t want to meet any of his lady friends or lie to H, I didn’t want to deal with any of it, anymore. But of course, I’d already missed the part where you get to just be a kid.

How do you reconcile a whole person with all their complexities? My dad was creative and openminded. He was not afraid to sing loudly in a public place just to make you laugh. He would doodle while he talked on the phone and when you next went to the phone you’d find something incredible there. He started sculpting at 70 because it looked like fun, he didn’t tell himself he was too old to try something new. He had notebooks and notebooks full of ideas for children’s books, YA novels, films and musicals. He was worried about the state of the world and worried for my kids and their whole generation. He lived almost 100 years. He was kind and he was a good listener and a good communicator. But he wasn’t a good husband and he wasn’t a good dad. He hurt a lot of people, certainly all the women in his life, certainly his son, certainly me. He helped a lot of people, too. He was my dad and I miss him. I am deeply sad. All those things can be true at once.

If you’d like to join me for a talk about reconciliation and complicated familial relationships I’ll be live here Friday 8/11/23 at 11:15am PST and if you’d like to meet me in-person, here are two upcoming possibilities!