All at Once

Time travel jet lag

Last June I went to New York City as I try to do at least twice a year. It’s my hometown and my step dad and brother are still in the apartment where I grew up - my “mom’s house” as I always called it, though she isn’t there anymore. When my mother was dying in the ICU and I was flying back and forth from Los Angeles every week, I realized Newark (EWR) was my best airport option. It’s easy to take the train to the city and you avoid rush hour traffic, which is helpful in a city that never sleeps and is therefore almost always in the throes of rush hour traffic. Last June, though, my cousin was able to get me at EWR and take me to my Aunt Louise’s house. If you’ve been spending time with me for a while, then you know my Aunt Louise, she’s one of the best people on the planet and I’ll stand by that. I spent my happiest childhood years with my Nanny, Aunt Louise and Uncle Richie and my four cousins at the Jersey Shore. Aunt Louise had a stroke last spring and I wanted to see her.

The previous time I’d seen her was when she came to the hospital to visit my mother. I can’t tell you the way she looked at my mom in that hospital bed with tubes everywhere and a ventilator breathing for her, or the way my mother looked back at her through all of that mess, but I can tell you it was everything. I could see the thirteen-year-old girl inside my mother’s ravaged body, and the way she peered out at the only person left in this world who’d known my mother when she was that girl. My mother was the flower girl at Aunt Louise and Uncle Richie’s wedding. Aunt Louise had watched my mother grow up. She looked at me the same way she looked at my mother that day, with absolute love and concern. She held my face in her hands the way she always has and she looked right into my eyes. We didn’t have to talk about it. We both knew my mother was not going to make it.

Months later when my cousin called to say Aunt Louise had a stroke, I realized we were in a new chapter. It’s the chapter where you start losing people you don’t know how to live without. The loss of my mother did me in for a year, and when I say did me in I mean I managed to keep breathing and doing all the necessary things for my kids, and all the things I have to do to keep a roof over our heads, but that’s about it. Most days I was pulled under, over, sideways and every other way by grief. These days, not quite two-and-a-half years later, there are countless times a week when I have a thought or memory and am suddenly in a flood of tears. I miss her in a way I didn’t know existed. My cousin said Aunt Louise was stable and was going to be okay, and she was right. By June my Aunt Louise was back at home with full-time care and lots of family around. For the first time since I was six or seven, I was going to spend the night at her house.

My cousin Diane is exactly the relative you want to get you at the airport. She’s the cousin you can call and get right to it, no need to waste time. She does not tolerate fools. She’s also quick to laugh, hug, cry. She calls me Ally-Oop like my aunt and the rest of my cousins. No one else is allowed to do this. She filled me in on how her mom was doing, and she’d made reservations at a really good Italian place for dinner. When we got to the house, I was reassured to see my Aunt Louise was her usual self. A little bit slower, maybe, but alert and extremely happy to see me. The house looked smaller than I remembered. What had looked to my four, five, six-year old self like a huge open kitchen with a big island in the middle and an eat-in breakfast booth in the corner was about half the size I’d imagined. The cookie drawer was in the same place and had long since been taken over by my cousin’s kids, and now their kids. The finished basement where we’d all played when I was little, the basement with my uncle’s pool table, and an overstuffed couch and tv where we’d watched movies, was now the guest bedroom. That’s where I’d be sleeping. I was going to use my aunt and uncle’s bathroom, the one where I’d been amazed/shocked/a little horrified to see that my aunt would sit and pee right in front of my uncle while he shaved and splashed on the Old Spice. I remember being stunned at their closeness and her comfort, and his seeming indifference to her peeing while he was in there. It was so different from my mother, who wouldn’t let me in the bathroom while she showered, or even in her bedroom unless she had on at least a bra and underwear. I never saw my mother naked until the very end of her life, when her robe would slip as she’d need to be moved into a more upright position in the hospital bed. By then, she had no vanity left, no sense that any of that mattered. I was the one who pulled her robe down to cover her.

It was wild to be back in that house, that house where I felt safe and loved as a child. I didn’t want to leave the next day, I could have stayed with Aunt Louise indefinitely. I think if I had, I might have started to age backward, that maybe we could have slipped through some portal together and woken up to find me and my cousins running around the basement as it was back then, full of board games and toy closets, the pool table and hide-and-go-seek games that went on for hours. But my visits back east are short, and there was something I wanted to do before I headed into the city. My mother didn’t have a will, she was an expert in denial and needed to believe she was going to survive ALS, even though no one ever does. When she died, I had to guess at what she wanted. The only thing we knew for sure was she wanted to be cremated. I’d spread some of her ashes around an olive tree in a vineyard in Tuscany as the sun was setting. I felt sure she’d like that. I’d spread some around a beautiful birch tree at her best friend’s chateau in France, and I felt sure she’d like that, too. But it had suddenly occurred to me that the very best place I could spread her ashes was at her mother’s grave, and her mother, my Nanny, was buried about twenty minutes from Aunt Louise’s house.

My cousin Diane had looked up the plot number and I took a Lyft over to the graveyard. It was massive and old and beautiful. I got out of the car with my rolling carry-on, and started walking through the cemetery. It was serene, and I was glad no one else seemed to be there to hear my wheels clattering along the pavement, disturbing the silence. There were giant trees on every side so the roads connecting all the plots were shaded and cool, but this place was so much bigger than I’d thought it would be. It looked like miles of gravestones in every direction. I felt like I could be here for days and not find my grandmother. Thankfully, right as I started to wonder about the practicality of my plan, a man in a pickup truck drove up and asked if I needed help. I showed him my printout and he told me he’d give me a ride, he’d been tending to the place for years and it was quite a distance. He put my bag in the flatbed and I got in and within minutes I was where I needed to be. He got out and pointed me in the right direction and said he’d be driving back this way in a while if I ended up needing a ride to the gate. I wondered later if he was real. I found the gravestone in the third row of graves I walked down, now wheeling my carry-on over bumpy, grassy terrain and being careful not to roll over any graves.

It was a big family stone that said Hamilton across the top. My Nanny and her husband, my mother’s father, were buried there together. I saw that the foot-stone only showed his name. I never met my mother’s dad, he died when she was thirteen. I looked around. I wasn’t sure I was allowed to scatter ashes at the grave, but I knew this was where my mother would want to be, and I knew my grandmother would want this, too. I decided that mattered more than any rules, and I knelt down at the foot of the gravesite and pulled my mother’s ashes from my pocket where I had them in a small glass bottle. Tears started streaming down my face instantly, but no one was around so I just let them spill. I put my palms flat in the grass and felt the coolness and the damp earth underneath. “Hi, Nanny,” I said, “I’m here. I grew up, I made it. I miss you.” I let myself fall apart for a while. Then I talked to my mom. “Mom, I brought you here to Nanny. It’s the one thing I know for sure you would have wanted. I love you and I miss you so much.” And I scattered her ashes all over my grandmother’s grave. I stayed there for a while longer and I said more things to both of them, things that are just for them and for me, but I made sure I said everything. And then I got up and wheeled my carry-on over the bumpy, grassy terrain which had only changed slightly since I got there, and felt the shwomp when I got it back up on the paved part and walked myself to the gate where I ordered a Lyft to bring me to the city.

Pulling up in front of the building I grew up in is, of course, the same as it would be for you to pull up to your childhood home. Knowing my mother isn’t in there is hard to describe. She lived in that apartment most of my life. She and my dad moved in when I was two, then just my mom and I stayed there when my dad left, and eventually my step dad moved in when I was seven. My brother was born when I was eleven. When I walk in these days, I can feel my mother’s absence immediately. It’s not just that she isn’t at the door waiting to greet me, or that I can’t hear her voice from the living room. It’s that she doesn’t reside there anymore and I can feel it on a cellular level.

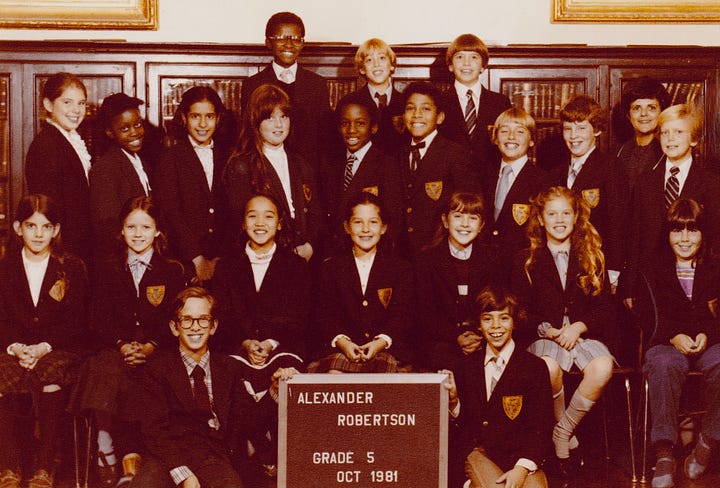

Sometimes I think the absence of someone or something can be as powerful as the presence. I get migraines. These days they’re usually well-handled by medication, but once in a very long while I’ll get one that defies everything. It’s like a reign of torture has descended upon my brain and it will relent when it relents and not a moment sooner. The day after I arrived at my mom’s and caught up with my step dad and brother, I went to my elementary school class reunion. It wasn’t a formal reunion, it was about fifteen of us who grew up together deciding it would be fun. I’d remained in “Facebook contact” with a handful of people I went through 1st to 6th grades with, but during the pandemic a whole bunch of us reconnected and zoomed a few times. It was insanely fun to see faces I hadn’t seen since I was thirteen. There’s something about the people you knew when you were a little kid, and when you see them, even decades later, you still see the little kid them. You don’t see the laugh lines or the grey hairs, you see Sam, with her blue eyes and freckles and mischievous grin, or you see Christian who blushes when he’s embarrassed and is the nicest guy in class. You see Jenny and Jessie, girls whose houses you slept at almost as much as your own, and who slept at your house, too, and even though they have their own kids and you have yours, when you’re together it’s like time travel. Your kids don’t exist yet, or they exist on another plane.

We went to our elementary school and walked the halls, and once again I realized how everything had been frozen in time in a perspective I’ve outgrown. Not that the place isn’t as special as I remember, I just remember it with the eyes and the height and the innocence of me at six, seven, eight, nine years old. Then we went and had drinks, which is something only grownups do, but I swear, in my head we were ten years old on a field trip drinking as if we were grownups. The next morning I woke up in the bedroom I grew up in with the most violent migraine I’ve had in decades. I hadn’t had much at all to drink, it wasn’t a hangover, or at least it wasn’t a hangover caused by alcohol. It might have been a nostalgia hangover, or time travel jet lag brought on by a night at my aunt’s house, a conversation with my Nanny and my mom even if I was the only one talking, sleeping in my old bedroom, and a walk through the halls of my childhood. It was so violent I lost my peripheral vision and raced to the bathroom multiple times to vomit. It was so awful there was no comfortable position to be in, no way to talk or think or know what to do. It was so intense I wanted to leave my body and watch myself suffer through it from somewhere else. It was so painful I started thinking about the ER. Then I called my doctor in Los Angeles. I paged him on a Sunday which I’d never done, and the beautiful man called me back. He listened to me for three minutes and called in prescriptions to the local CVS. Anti-nausea medication so I’d stop vomiting and some kind of magical pain medication that brought me relief within an hour. The absence of pain is a thing that’s hard to describe, but if you’ve been through it you know the rush of gratitude that sweeps in when you stop wanting to die. When you can start to feel the vise grip loosening and the desperation waning. It’s a stronger, faster version of what happens after a heartbreak. That first morning you wake up after months of opening your eyes and remembering right away, and on this morning, maybe you get seven minutes of peace before you remember. And that seven minutes is enough to convince you you’re going to survive.

I don’t know how we keep going through the loss and the time travel. All those old versions of ourselves still running through the halls. The moment you had your first kiss with the sun streaming through the windows, and how that moment is still happening somewhere. The first person who betrayed you, and the second and the third. The first person who left, or the person who left you before they left you. The time you fell smack in the fountain at Lincoln Center, or made the most illegal U-turn on a freeway so you wouldn’t be stuck going the wrong way for miles and miles, and no one saw. The time you moved across the country with a cheese-stealing shoplifter and found out at Whole Foods one day, or the time your dog, your beloved dog, woke up one morning and couldn’t walk in a straight line, and how three hours later you watched the light go out in his eyes, bereft and pregnant and a week away from going through a childbirth you thought you might not survive. Hours of being on one side of the veil, then the other. A crash course in proximity and the illusion that death is some finite thing that happens at the end of your linear life, when in reality, you could almost reach out and touch it anytime. The one word in your head as you fight for your own life and your unborn child’s - please - or, when you’re exhausted and unsure you simply pray that whichever way you’re going, you go together. I don’t know how we take all the losses and upheaval, but I do know they make us less sure of everything. More aware of the fragility of every single thing, the way you’d better not pull on a thread unless you’re ready for everything to unravel. Maybe it’s good we start over again and again, and that we lose almost everything along the way. Maybe it’s good that we soften as we go, that we can’t always find our way, that we’re more surprised when the ground feels solid than when it doesn’t. Maybe that’s what makes us better, kinder, more grateful, more inclined to run in the direction of love when we sense it, to do the crazy thing, to not waste time. The absence of things and the presence of things and the way time folds in on itself. Maybe no one is ever really lost, and the only person you can really be lost to is yourself. Maybe it’s possible we’re all existing as everyone we’ve ever been and everyone we’ll ever be and we catch glimpses of those other selves when we least expect it and when the light is just right.

If you’d like to meet me in real time for a conversation about loss, time, grief, joy and all the versions of us still running through the halls, I’ll be here 3/22/24 at 11:15am PST or you can wait for the Come As You Are podcast version. And there are still some spots left for Portugal if you want to meet me there in June, it’s going to be incredible and I’d love that so much.

Oh wow, this was absolutely amazing Ally! I am writing this from my parents flat back in Slovakia, luckily they are both alive and relatively well, but both had some form of cancer that is under control or at least that's how I understand what they say, though I know eventually they will die, unless of course I die first and I'm not sure which I'm terrified most. Strangely, your writing makes me feel peace. I can't describe it, but recently I've been pondering and I have a few writers who are my absolute favourites, Erin Hanson, Nikita Gill, Sarah Manguso, Amy Dressner and I think this is obvious, you. I guess even if your goal isn't to write any manual how to feel happier in life because let's be honest, happiness is so fleeting, but what you always manage to do is make me feel alive and grateful. Of course I know the day my mum or dad die my heart will know heartbreak it never experienced and I suspect I'll be a wreck, but at the very least I'll have some recollection of your story and perhaps that's enough for a start. I wish you and your beloved all the best, always. Namaste xo