In the Face of Loss

What we hold onto and what we release is everything

At the end of 2021 - December 7th to be exact - I lost my mom after a horrific and devastating battle with ALS. I’m calling it a battle as if anyone could win, when at the moment there is no cure. The only battle available is the fight to get through the grief and powerlessness you feel watching someone you love, suffering. I haven’t experienced the multiple horrible ways there are to lose a person, but I have no doubt at all ALS is one of them. The disease took everything from my mother - her ability to form words and speak, to chew, to swallow, and eventually her ability to do anything at all except die in a hospital bed a week after signing a DNR/DNI. If you had known my mother, you’d realize what an unthinkable turn of events this was.

My mother was a force. She would walk into a room and there was no way to miss it. She was always put-together - hair done, makeup done, perfume just right, outfit, jewelry, handbag, shoes. And then there was her personality - she was smart, funny, kind, and she had a biting sense of humor. People loved her. She was also a high-functioning alcoholic and alcohol brought out the worst in her, as it does in so many people.

Her rage would bubble to the surface when she drank, and though I’d try to keep her from drinking, or mitigate the the repercussions when she did, I was her target. She’d go for the jugular, use things I’d confided in her in moments of vulnerability to stab me in the heart at my lowest moments - until I learned never to confide in her at all. It was a tough relationship for me because I loved her so much. She loved me too, but her expectation was that I would pretend the terrible things hadn’t happened, and I didn’t know how to do that. Boundaries became the way I managed things between us.

In the midst of my mother’s rapid decline, my dad - who’d left my mom when I was four and gone on to marry two more women - was in an assisted living facility with his fourth wife. She happened to be his high school sweetheart, and was suffering from Alzheimer’s. She needed to be moved into the memory care unit, and my dad couldn’t go with her. My half-sister Carrie - my dad’s daughter from his first marriage - called me. She and I had only just started talking regularly.

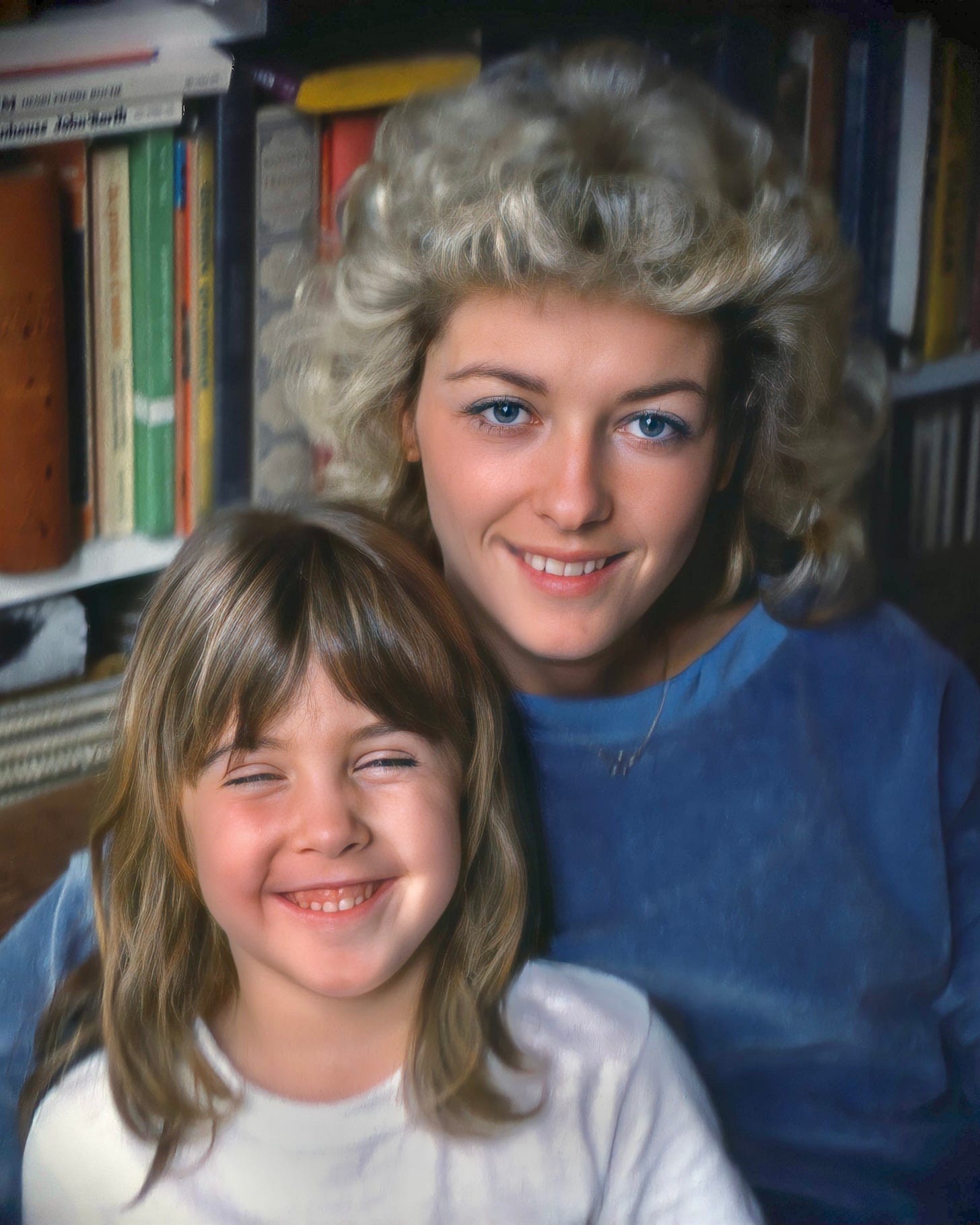

Carrie’s mother, my dad’s first wife (believe me, I know this is confusing), couldn’t bear for Carrie to have a relationship with me - the product of the affair that had broken up her marriage. After all, her husband - my dad - had an affair with my mother - a girl only three years older than their own daughter at the time. I’d be pissed, too. I’d only met Carrie a handful of times as a kid - she came to New York City when I was six, and we went to visit her in Georgia for a week when I was eleven. I thought she was the most beautiful girl I’d ever seen in my life.

When my dad was ninety-three and still living in an assisted living facility in North Carolina with his wife, I asked him to ask Carrie if I could call her. Her mother had passed away a good fifteen years prior, so I knew her feelings would no longer be a factor. I figured it would be good for us to be in touch so that the next time we spoke or saw each other wasn’t at our dad’s funeral. I didn’t say that to my dad, of course.

Carrie was happy to be in touch, and we developed a pretty fast friendship. We felt each other out for a while, I was certainly careful at first and she was, too, but it wasn’t long before we were trading stories. She told me how he used to mow the lawn in his white speedos in the cul-de-sac where their house was, and how she begged him at sixteen to please wear shorts and a t-shirt like the other dads. He wouldn’t. I told her about all our dad’s “lady friends” I met as a little kid, and some of the crazier moments I experienced with him along the way. It was good to have someone to talk to who actually understood what it was like to be his daughter.

This was all during the pandemic, mind you, so there was no easy way to fly anywhere or do anything except feel horrifically helpless. I FaceTimed my mother several times a week and joined all the Zoom meetings with her team of twelve doctors, but it was hard not to be able to be there with her, even if she was blaming me for her ALS. (Yes, you read that correctly, and yes, there’s a longer story there.) This was before the COVID-19 vaccination, so even if I had flown to New York, I’d have to quarantine for three days, test, see her, test, then fly back and do the same thing on the other end to be sure my family would be okay, which would mean costly hotel stays on both ends. I couldn’t be away from my kids who were in zoom-school all day for two weeks. It was not an easy chapter. Carrie said she was going to drive to get our dad and bring him back to Georgia to stay with her and her husband while she found an assisted living facility near where they lived. She said I had enough going on with my mom, and I couldn’t fly to get our dad, anyway. She said she was retired with no kids and she was going to handle it. To say I was grateful and relieved is an understatement.

Carrie took care of everything. She got our dad’s Veterans’ benefits figured out, found a beautiful assisted living facility not too far from her house, took my dad to a million doctors appointments, and generally made sure he had everything he needed. It took about nine months to get all of that situated, and while that was happening, she moved our dad into her house. It did not go well.

They butted heads almost every week. Carrie would call and tell me our dad had kicked her dog, or yelled at her because things weren’t happening quickly enough. He wanted to find an apartment to live in, not an assisted living facility, even though he needed the help. He would call and tell me how difficult she was, how controlling. There were echoes of conversations I’d had with my dad when I was a tiny child, times when he’d complain to me about all the difficult women in his life and cry in my arms, but now I was a grown-ass woman. I could see that my dad was the unreasonable, ungrateful one. I told him Carrie was a godsend, that she was doing things for him I couldn’t have done at that time, that I had my hands full watching my mother deteriorate and trying to help there, and that he should be thankful and act right.

What I didn’t say is that he’d abandoned Carrie and her brother, and he was lucky she was doing anything at all. But I thought it, loudly.

Nonetheless, Carrie would call and tell me she had driven to and from the assisted living facility to see him (an hour each way), taking him to lunch and to run errands, only to have him blast her for not handling things well, tell her the Power of Attorney he’d given her wasn’t working out, tell her he was moving back to North Carolina where he’d find an apartment on his own. At this point in time, our dad’s knees were in bad shape and walking more than a short distance was not easy. His hearing loss was severe. His eyesight wasn’t great. He certainly wasn’t safe to drive. The idea of him trying to find an apartment on his own was ludicrous.

One day Carrie sent an email to our dad and cc’d me. She said he should go ahead and grant me the Power of Attorney and do whatever he liked with his living situation. She said she was done, she wouldn’t be visiting him anymore or speaking to him or anything else. Then she called me. She said she was sorry but she just couldn’t handle the stress any longer, that he was rude and ungrateful and she was exhausted from it all. I told her he was crazy not to thank his lucky stars for everything she’d been doing. Then my dad called me crying and said Carrie was so upset and he felt terrible and he was going to fix it. I told him he was lucky to have her and that he should try to make things right because she’d done so much for him.

The truth was, I had been wondering what was driving Carrie to do even half of what she’d done. She drove from Georgia to North Carolina to help him pack all his belongings when he and his wife moved to the assisted living facility in Pennsylvania, where they had better memory care. Then she drove to Pennsylvania and helped him pack and move to Georgia. That’s an awful lot of support to extend to someone who left you at sixteen and didn’t really look back. I don’t remember my dad visiting his kids in Georgia where they moved after the divorce. I doubt he sent child support since he was unreliable financially and often didn’t give my mother child support after their divorce. I wondered if Carrie was hoping for some kind of healing and closure before he died. It made me angry that my dad couldn’t even give her that.

Our dad apologized and Carrie resumed visiting him and taking him to his doctors appointments. She’d often FaceTime me when they were together, or send me pictures from Dunkin’ Donuts, our dad’s mecca. By then, my mother had passed and I was not okay. Some days I felt the grief was going to swallow me whole. My mother had been gone five months. I’d gone to visit her in August after my kids were vaccinated and we could safely fly to see her without risk of exposing her to COVID, which would have been a death sentence faster than the one she already had.

It was hard to fathom what had happened to her. She was just bones and skin. She had an app she used to type in the things she wanted to say, and the app would read them out in a robotic female voice. She spent most of the day trying to drink a shake my brother made her. She’d stand at the sink, take a sip, lean her head back, lift her bottom jaw to meet her top because the muscles had gone slack, and sway. That was how she got a sip of shake down. She had a napkin in her hand at all times because she would drool since she couldn’t keep her mouth shut. She dabbed at the corners of her mouth every fifteen seconds or so. I cannot explain the way my heart shattered.

I spent the last month of my mother’s life with her in the ICU twelve hours a day, advocating for her, trying to keep her comfortable, reading to her, reminding her of happy times or funny memories, making sure she had whatever she needed and wanted. I made overnight trips back to Los Angeles once a week to look at my kids and husband, make sure everyone was okay, and get back on a plane. I didn’t let myself think about the financial impact it would have, I just flew. My mother and I healed our relationship while she was on her deathbed, and in my lighter moments I laugh about that. It is so like my mother to have to be on her deathbed before she’d consider that maybe she’d been wrong. That maybe I did love her with all my heart. That maybe the drinking and the rage it unleashed in her had been the problem.

When I got the call from Carrie’s husband that she’d had a sudden stroke and was in the ICU, I couldn’t believe it. He unknowingly sent me a photo of her that looked so like my mother in her last days I ran to the bathroom and threw up. He said things didn’t look good. He said the stress from my dad had been too much for her. He said I needed to take over everything she’d been doing for our dad, right then.

I sent all the emails and made all the phone calls, but it was daunting because much of what she’d set up could only be modified by her. Neither Carrie nor I had any reason to imagine anything like this would happen, so she hadn’t shared email addresses or account numbers or contact information. The custodial account she’d set up for our dad’s Veterans’ Benefits would need to be taken over by me, which meant a criminal background check and a mountain of paperwork. My dad had to give me Power of Attorney, which he didn’t want to do, he didn’t think he needed it. Carrie didn’t want to see him, she was fragile and on life support. She didn’t make it.

The thing about grief is that it does you in, even as life around you continues. Lunches still need to be packed. If you’re me, yoga classes still need to be filmed. Your dog still needs to be walked. Your teenagers still need your support, even if they don’t always want it. I’d experienced my first panic attack twelve hours after my mother died. Most days I was just keeping my head above water, and that’s with yoga and meditation and breathing exercises and every other tool in my toolbox. I’d heard the term Sandwich Generation, but as with most things that don’t directly impact you, I hadn’t really paused to consider what that was. You can’t really know what it is until you’re eating it, anyway. Zero stars, do not recommend. And yet, you’ll probably end up eating some version of it.

I tried to take care of everything for my dad from California, while he was in Georgia. It was not easy. Picture me, standing in my den in Santa Monica, texting my dad to tell him I was about to call Social Security, I’d likely be on hold three hours and needed to be sure he’d be available when they picked up. Picture me seeing the “Read receipt” but not getting a text back for an hour. This is now a ninety-five-year-old man, so the fact that he could text at all is impressive. Picture him texting Understood. Imagine me getting a human being on the phone after three hours of listening to the “hold” music, texting my dad to say, I’m calling you now okay? I have someone on the line. Please pick up because they need your permission to talk to me. Picture the Read receipt, me calling, my dad not answering.

Now picture all of that again for AT&T, Veterans’ Affairs, the bank…everything. He started talking about finding an apartment in North Carolina again. I told him I thought that was a terrible idea. He asked about apartments in California.

This is when I started to grapple with what I owed my dad. What do you owe the man who broke your mother’s heart, the women before her, and all the women after? What do you owe the man who almost singlehandedly destroyed any chance you had for an innocent, carefree childhood because he made you his tiny therapist? What do you owe the man who is a good friend to many, an adored uncle, a talented artist, but not a good dad?

The thought of moving him to California and taking over his care did not fill me with joy, it filled me with incredible anxiety. I have two kids, a business, a book I’m trying to finish, tons of pressure and responsibilities, and a husband. In the midst of all that, I was grieving the loss of my mother and just barely making it. My days were packed. I knew what Carrie had been doing, I was already doing all of the fiduciary things along with setting up rides to and from doctors’ appointments and talking regularly to the nurses and aides at the care facility in Georgia. My dad was talking about finding an apartment near my house so he could walk over and spend time with us, but I knew he’d need to have help. I started looking at assisted living facilities near me.

I found a place about thirty minutes away. Family-owned, the residents looked happy, everyone said the food was great. I sent pictures of the room to my dad. There were two available rooms, and I picked the one that was sunnier because I knew he’d want to sculpt and was going to want the light. I called truck companies to get price quotes on moving his belongings across the country, and realized it would be cheaper to replace everything but the belongings that were sentimental. My dad was excited and energized. He began packing. One of my cousins and her husband who lived nearby helped him get to UPS, took him to the airport, and right to the Delta travel assistant who wheeled him directly to the gate and made sure he got on the plane. There was another travel assistant waiting to wheel him to me and my husband at LAX.

My dad had objected, he said after the flight across the country he would take the bus from LAX to the assisted living facility in Van Nuys on his own, and walk to the facility from the bus-stop with his travel bag in tow, a few miles away. When I said that was absolutely not a viable plan and not what was going to happen, he yelled at me. I told him if he couldn’t agree to that, then he’d have to stay in Georgia.

This began the often contentious dealings with my dad. He would swerve regularly from expressing gratitude for everything we’d done - my husband spent two weeks setting up his room, arranging his sculpting station just the way he wanted it, putting all his furniture together, printing out and framing photos for him as a surprise so the place would feel like home, putting up shelves, hanging clocks, meeting Spectrum there to set up his tv, making sure the coffee maker and microwave were good to go, and so on - to yelling at me when anything didn’t go according to his plans. I realized I’d better set boundaries quickly, so I let him know if he yelled at me, I wouldn’t visit that week. I told him it was okay for him to let me know when he needed anything at all, but not okay to raise his voice.

It was a refrain I’d have to repeat often, but it became part of the routine. I’d drive to see my dad each week. Usually he’d need to see a doctor, so I’d work that into the schedule. Then I’d take him to Walgreens where he looked endlessly for the razors he wanted but could never find, curse the countless options, buy 3 six-packs of Mott’s Apple Juice, and then we’d head across the street to Dunkin’ Donuts. Some days he’d be in good spirits and we’d have a nice time, and other days he’d be cantankerous and difficult, and it would be a slog.

His hearing loss was also a huge issue and I knew it would be hard for him to make friends if he couldn’t communicate, so I got him an appointment with a mobile hearing specialist who came to see him in his room and did hearing tests for two hours. He called me after the session with my dad and talked to me for thirty minutes about the loss of hearing in each ear, and how these new hearing aids would help and make it possible for my dad to hear even in a busy restaurant. My dad told me the guy had no clue what he was doing and had to test over and over again. When I explained that he was not redoing what he’d done, that he’d just done a very thorough job, my dad refused to believe it. Until he got his new hearing aids and could hear well for the first time in years.

Sometimes I’d rent the little private dining room at the facility and bring the family for lunch or dinner. My son would bring his guitar and play for my dad in the courtyard. My dad would text me every few days with requests for things he wanted me to order and have delivered, like sculpting clay, a beard trimmer (I accidentally bought him a manscaping trimmer, something my teenagers still howl about), new sneakers or sweatpants.

As time went on, my dad’s health started to deteriorate. He became mentally foggy. He’d talk to me about the secretary he met years ago, not realizing the person he was talking about was my mother. He’d tell me the Power of Attorney wasn’t working out and he was going to rescind it because doctors appointments were taking too long. But he’d also send nice texts thanking me for everything I was doing. It was a mixed bag and I never knew what to expect. It was exhausting and stressful a lot of the time, but gratifying, too.

At no time did I ever have the desire to bring up ancient history. My dad had never been one for apologizing, I’m not even sure he felt he’d done anything wrong. He definitely fell somewhere on the narcissism spectrum, as anyone would have to who’d hurt so many people along the way. That doesn’t detract from those he helped. People are complicated. You can be a good person and not a great parent, or a regularly selfish person who is sometimes unselfish, or who is able to be unselfish in some ways and not others. You can’t paint people with one brush or another, much as we like to.

My dad was a dreamer and his dreams bordered on the delusional much of the time, not just in old age. When I wrote about some of the impact his behavior had on me in Yoga’s Healing Power, my publisher required I get him to sign a waiver so they wouldn’t be sued for slander. I had to do the same with my mother. My dad read my book and said it felt like another lifetime, he didn’t even remember most of what I’d written about, and he signed. That’s the closest I ever got to an apology from him, and I stopped needing one decades ago.

When I weighed what I owed someone who had been a pretty awful father, I realized his behavior wasn’t really the issue. The kind of dad he was wasn’t the thing. The thing was whatever my standards are for how a person should be treated at the end of their life, or ever, really. I don’t have to meet his eyes in the mirror at the end of the day when I’m brushing my teeth, I have to meet my own.

I suppose I could have said screw him, he was a terrible dad and I don’t want to take on the pressure and responsibility of being his primary caregiver at the end of his life. I could have left him in Georgia. I could have decided all the years of therapy and all the ways he let me down meant I didn’t owe him a thing, including my guilt. But there’s no way I would have felt good about that. He made the mistakes he made. He was the person he was. It wasn’t all bad, he had a lot of great qualities, too. I’m glad I showed up for him, despite the kind of dad he’d been. I don’t think he set out to hurt anyone, I just think he was mostly focused on himself. I think he loved me and thought I was great, I think he was proud of me, I just think his ability to really love anyone was limited by his self-absorption. His best wasn’t great. That doesn’t mean I have to meet him on that level.

This can be a tricky concept, because you don’t want to set yourself up to accept crappy behavior from people and then treat them with kindness. If someone is hurting you, you have to protect your heart and draw the line. With my dad, I had already processed and accepted who he was, I wasn’t expecting anything different. His behavior didn’t surprise me, and it didn’t get me too riled up. Not often, anyway. I certainly didn’t take it personally. When you can get to that place with someone, it really doesn’t matter what they do or do not do, you can just focus on how you choose to respond. The best thing for me was to respond with kindness and as much generosity with my time and energy as I could muster. I wanted him to leave this earth feeling at peace, and feeling cared for … I think I would have felt truly awful if he’d gone out any other way.

Most people just want to feel seen, cared for, heard, understood. They want to feel loved and cherished. A lot of people are in pain, and that pain drives them to make some awful choices. I guess we can hold onto the ways people have let us down, cling to our list of ways we’ve been wronged, and decide that’s why they don’t deserve forgiveness. But for me, it feels so much better to let those lists go, because there’s enough rage here on earth. There’s enough pain and anguish, enough blame and bitterness, enough pointing fingers.

This whole way of thinking about people and thinking about life as one way or another is killing us. It’s extreme and it’s violent and it isn’t realistic. Human beings can be so brutal with one another, so angry and unforgiving, so quick to judge, vilify, cast out. Anywhere you can be gentle is good. Anywhere you can let go is good. Anywhere you can forgive is good. Anywhere you can start a new story is a place where freedom exists. People are going to people and life is going to be life-y, and you still get to decide who you’re going to be in the face of that. Hoping for more freedom and gentleness for us all.

If you’d like to meet me in real time for a talk about what we owe people, what we owe ourselves, the Sandwich Generation, grief, and forgiveness, I’ll be here Friday 10/20/23 at 11:15am PST, or you can wait for the Come As You Are Podcast version. And if you’d like to meet me out in the world, I would love that so much. There’s still time to get in on Joshua Tree in November, and we have an incredible group signed up for Portugal in June! They’re both going to be magical and I’d love to see you there.

Dear Ally, I just read this older post and it touched me deeply. Your title tag, 'what we hold onto and what we release is everything.' I will reread it often, you embody a rare form of loving, what I think David below described well as 'bodhisattva-esque'. I am smiling with gentleness at your way of life and it deepens my belief we can be goodness. Thank you.

Ally, so sorry for these losses. What an incredible story you have told. Thank you so much for writing all of this, every word.